Slightly over a century ago, in January 1918, doctors at a military camp in Haskell County, Kansas, USA, were puzzled by cases of local soldiers with severe flu symptoms. In the most extreme cases the signs of severe illness included hemorrhaging (i.e. massive bleeding) from the nose, ears and stomach. A painful and rapid death followed the symptoms with a very high probability, with the official cause of death being pneumonia or massive hemorrhaging itself.

At first – what much later became known as the Spanish flu – the illness was misdiagnosed by observers as cholera or even typhoid, both of which have similar symptoms. But, by early March 1918, American doctors and pathologists realized they were dealing with a very different beast. By then it had mushroomed into a global monstrosity that spread via sneezing and coughing, by tiny and very deadly virus particles.

The precise origin or patient zero of the Spanish flu pandemic is controversial (note: a pandemic is an epidemic that has spread around the world). Some claim that it originated in other locations within the U.S. in mid-1917, and other researchers argue that the flu originated in East Asia and in particular China. I’ll refer interested readers to the (ever-changing, somewhat unreliable, reviled) Wikipedia page, in addition to some more respectable references with sources on the latest volley in an ongoing debate about the cause of the virus. What isn’t in dispute is that (i) it originated in ducks and pigs and then jumped to humans, (ii) it is a strain of the H1N1 virus and, most importantly, (iii) it spread around the world by soldiers engaged in the conflict of World War I.

Recall that in early 1918 – that is before the famous Armistice Day of November 11, 1918 – the world was deep in the fog of battle, with troops moving around Europe and living in close quarters within the theatre of war. All of this created a fertile breeding ground for the Spanish flu virus, which marched around the globe from one pliable host to another with remarkable speed. Needless to say, antibiotics had not yet been developed and commercialized, but even if they had been, they could not have stopped the virus.

Ironically, in the year 1918, the war effort itself spread the virus but also obscured or shrouded it. Many countries in Europe as well as the U.S. were rightfully hesitant to allow open reporting of the new and deadly flu – for fear it would impact the troops’ morale – and used the war censorship process to conceal the extent of the pandemic. Media reports among both the Allied and Central powers, were limited and tame. The newspapers were devoid of the (scary) headlines one might have expected from a salacious press. Compare this to the headlines during the bird flu in the 1990s or the SARS scare during the early years of the 21st century. As far as the government was concerned, officially speaking, if people (soldiers) were dying from an unknown illness, battles and fighting were officially to blame.

This also helps explain the Spanish origins for the name of the flu. The country of Spain was one of the few neutral countries (in addition to the Scandinavian countries) during the war, so the Spanish media were free to report on anything they liked, including the new and deadly flu making its way around the world. Alas, when Spain’s reigning king Alfonso XIII was infected (in the spring 1918) with the flu (for a second time, actually) and suffered the above-noted symptoms, the world’s media included regular updates on his status. So, as far as history is concerned, the pandemic will always be associated with Spain (although in Spain the virus was nicknamed the Naples Soldier).

For the record, King Alfonso XIII survived the 1918 flu and recovered fully despite the ruthless odds. But history wasn’t kind to him. A mere 10 years later he was accused of high treason by his countrymen and he fled the country in disgrace in 1930, settling in Rome. He then abdicated the throne and died (peacefully) in 1941, more than two decades after recovering from a bad case of the flu. He will be known (in infamy) as the person who bequeathed the name Spanish flu to the world, as well as indirectly spawning the cruelties of the Spanish civil war and General Francisco Franco.

| Facts About the Spanish Influenza Pandemic | |

| Time Period (over 3 waves) | March 1918 to May 1919 |

| Global Infection Rate | 1/3 of World Population |

| Mortality Rate (if infected) | Between 10% and 20% |

| Global Death Toll | Min: 50 to Max: 100 million |

| Mortality Extremes | Iran (20%) vs. Japan (0.5%) |

| American & Canadians | 725,000 deaths |

| Likely Cause of Death | Pneumonia (cytokine storm) |

World War I, which technically ended with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, killed approximately 17 million people. In contrast to the death toll from this human-made conflict, the Spanish flu surrendered after having killed at least 50 million people around the world, and possibly even double that number.

Now, the large margin of error (tens of millions) in estimating the death toll is unfathomable in today’s world, but one must remember and be cognizant of the difficulties in properly accounting for a cause of death – or even identifying a death – during such a turbulent period. One thing is for certain, the Spanish flu was deadlier than World War I, although with fewer memorials, statues or statutory holidays. History books might have forgotten the details, but at the time of the outbreak, the American public was well aware of the war with germs (as well as Germans) and took precautions.

For the record, October 1918 was the worst month, and churches, schools and theatres were closed. Victory parades were mostly outlawed, but bars and taverns remained open as long as patrons took the bottled beer home with them to drink in private. Face masks were enforced in public, mainly to prevent the estimated 40,000 droplets that were released every time someone sneezed from infecting others. In fact, New York City passed an ordinance imposing jail time and fines for people who didn’t cover their mouths when they coughed. (Perhaps that’s an ordinance that should be resurrected in the current COVID-19 environment!)

From Morbidity to Mortality

Approximately one-third of the world’s population was infected (morbidity) and became ill during the influenza pandemic. That is, approximately 500 million people became ill around the world. From that large unlucky group, between 10% to 20% died from causes related to the virus, leading to a mortality rate of between 3% and 6% globally. More recently, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta estimated that the (unconditional) mortality rate from the Spanish flu was 2.5% globally, which is slightly lower than the 6% figure suggested above. The extra deaths, they claim, were attributed to World War I, not the flu. Anyway, the debate goes on. Some countries and regions were affected much worse than others. See comparisons for Iran and Japan, for example.

Closer to home, 675,000 Americans (from a population of approximately 105 million) and 50,000 Canadians (from a population of approximately 8.5 million) died from the flu during an approximate 18-month period. The implied mortality rates in North America, which were approximately 0.6% for both Canadians and Americans, were lower than the global mortality rates. These rates are consistent with the fact that North America suffered relatively less from the Spanish flu compared to other regions, such as Europe and Asia.

Getting back to the topic of variability, Iran lost 22% of its population to the Spanish flu, while Brazil’s isolated communities in the Amazon delta weren’t affected. The reasons for these regional variations in mortality rates are still being debated a century later. For example, the governor of American Samoa imposed a strict quarantine on the island, which explains the reduced infection rate to virtually nil. Yet another possible explanation for the variation in mortality rates across countries is the age distribution of the population, which brings me to my next point – and perhaps a shocking one.

The Longevity Shock

Separate and distinct from the variation in mortality, was how the mortality rates varied as a function of the afflicted person’s chronological age. In particular, what was completely unexpected at the time was the age distribution of who was infected and who died. This gets to the essence of the longevity shock I mentioned earlier. Normally one might expect that older, naturally frail and weak people would be the most vulnerable to such a pandemic, with a higher propensity for infection and death. But the reality was surprisingly quite different.

First, 99% of the deaths in the U.S. from the Spanish flu were individuals under the age of 65, and half of the deaths from the flu were young and middle-aged people between the ages of 20 and 40. One might say the virus preyed on the strong and energetic, while the naturally weak and diminished survived.

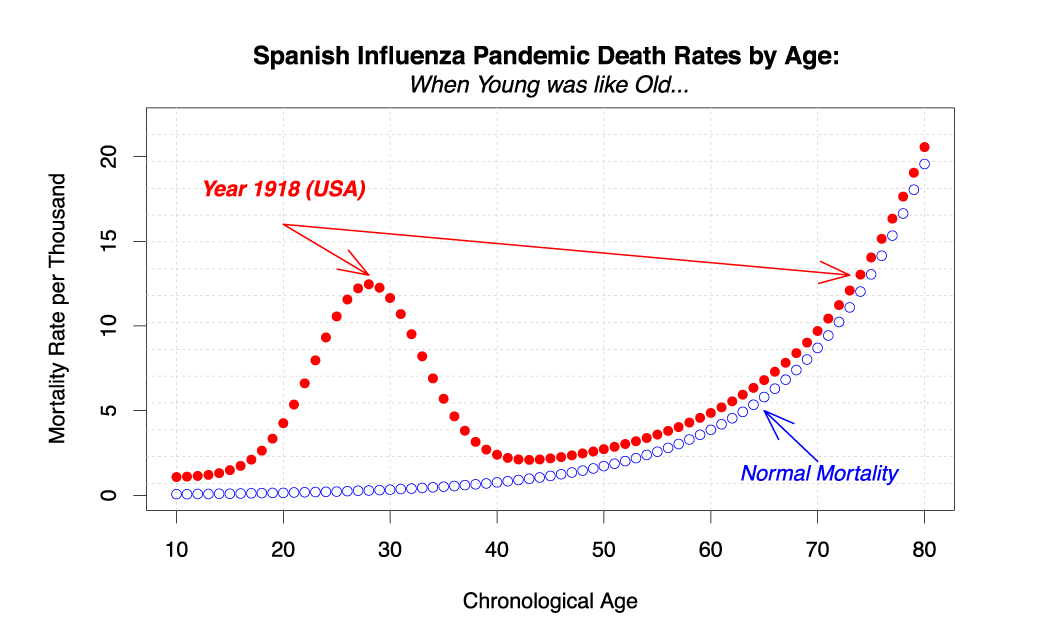

This was – and continues to be – quite mystifying for epidemiologists who study (and puzzle over) these matters. But it’s more than just young versus old. Figure 2.1 displays the mortality or death rate from the Spanish flu as a function of age, with a noticeable spike around the age of 28. It’s quite a jarring picture and should elicit a wow moment. It did for me. This is what I refer to as “the longevity shock.”

Going back to the concept of biological versus chronological age, looking at this figure it seems that during the period of the Spanish flu, although your chronological age might have been 28, your biological age was closer to 75. The mortality rate was the same! But why?

Well, if you think of biological age as being closely associated with mortality rates, and rates between 20 and 40 spiked, then your biological age spiked as well. Suddenly, overnight, you aged by 20 to 40 years as measured by your life expectancy. Researchers have estimated that life expectancy dropped by 12 full years due to this spike in mortality. The equivalent of hyperinflation for mortality. And again, it was the youngest (chronologically) adults who experienced the highest death rate.

Now, like many other aspects of the Spanish flu narrative, the reasons for this puzzlingly low mortality rate among the elderly, has been subject to much scientific speculation. Some have conjectured that older adults might have developed an immunity of sorts because they would have been alive and exposed to a pandemic 30 years earlier in the 1890s (known as the Russian flu). Others have suggested gender stereotypes as a factor. Supposedly, “real men” didn’t need to rest when they were infected with the flu – something they obviously did require in hindsight – which ended up killing them with greater frequency, relative to those who took time off and went to bed. But there was obviously more to it than lack of rest.

The younger (and stronger) the biological immune system, the harder it was to fight off the Spanish flu. The more an individual was willing and able to fight the disease, the more it fought back. And, it usually won. I would call it the 20th century’s first and greatest longevity shock.

Here is just one interesting anecdote about what this Spanish Lady did to many young strong American (and actually Canadian) men. The only time in history that the Stanley Cup hockey finals ever had to be canceled was in 1919, during the third and final wave of the Spanish flu, which hit in the spring of that year. Even during years of war, the famed hockey league managed to cobble together enough reserve players – the real teams had volunteered and went off to fight – and managed to complete a full season. But in the spring of 1919 the final series was canceled when most of the Montreal Canadiens (a perennial favorite at the time, because they had won the most games) were bedridden. After five games the championship was cancelled. One is hard pressed to think of a group of people who are more suited to fight a disease or war, on or off the ice.

Enter Life Insurance

Now, some readers might find it callous of me to focus on (hockey or) the rather trivial aspects of money in the wake of what has been described as the greatest medical holocaust in history, but the insurance industry is quite central to the story here. For all intents and purposes, insurance companies were the only ones that could protect families against the financial consequences of this longevity shock. By pooling small amounts of money from large groups of policyholders who paid regular periodic premiums, the companies were able to create a very large fund that could be used to support and pay the beneficiaries. For example, 10,000 people might pay an insurance premium of $100, creating a pool of $1 million. And, if 1% of the pool died, each beneficiary would receive 1% of the pool, that is a $10,000 death benefit. They paid $100 and received $10,000. It might seem to be magic, or perhaps a ponzi scheme, to those who aren’t familiar with the principle of insurance. That’s the essence of risk pooling.

As noted earlier, one quarter of the U.S. population was infected by the Spanish flu, and although most recovered, an average of 1,250 Americans died every single day over a period of 18 months, leading to a loss of 675,000 lives.

Many – although certainly not all – of those who died owned life insurance policies, which committed the insurance company to pay the beneficiaries hundreds of thousands of dollars. Although it was unclear at the time whether these insurance companies could sustain such financial pressure and survive the flu themselves.

Not unlike many other industries in the economy, insurance companies lost employees (and executives) and obviously had a difficult time maintaining day-to-day operations. A beneficiary couldn’t receive a death benefit payout or check if the agent himself – and perhaps his entire back office – was infected with or died of the flu.

Some agents (who weren’t infected) reported issuing or selling a policy to a family one week, barely having collected only one single premium payment, only to return the next week to pay the family because the insured, perhaps a parent or father, had died. The National Underwriter (a popular industry magazine) wrote the following on January 16, 1919. It was still in the midst of the flu, but a few months after the worst had passed. “Almost all agents have had startling experiences during the last few months of soliciting people for insurance, who in a few days were stricken with the flu and died.” Kudos. I suspect that if this happened today, a death so soon after the policy was issued, the claim would be challenged or disputed by the company. Ah, the good old days.

Back to pooling again, as I explained with my simple example, the only way the principle or model of life insurance works is if many people pay small premiums to the insurance company over long periods of time – and don’t die quickly – so that the company has enough reserves to pay the few who perish along the way. The essence of risk pooling is the risk of having many people buying insurance who never make a claim or do so very far into the future. Could the insurance industry cope?

Well, the insurance companies survived, and they thrived. I would argue – and I don’t say this lightly – that the Spanish flu was one of the best things that happened to the insurance industry (at least in the U.S.) in the early part of 20th century. This might sound quite odd, crass and perhaps even cruel, but it’s true. The flu was a godsend to anyone whose business it was to sell life insurance.

According to estimates published in the 1920s in the same National Underwriter – a publication which actually survives to this day, by the way – the insurance industry paid out claims totaling 0.5% of the U.S. GDP as a result of the Spanish flu. In today’s dollars that sum would be approximately $30 billion. This can be compared to (approximately) $80 billion that the insurance industry paid out in the year 2018, for example. When you consider this was paid out a century ago, it’s an astonishing sum of money.

Don’t get me wrong. It was a scary and stressful time for the industry. Some insurance companies (mutual companies, really) had to suspend dividends to shareholders and policy holders. Others required emergency loans from banks to help with liquidity constraints and the inability to sell investments. In fact, there were cases of insurance company checks that should have bounced due to insufficient funds in the relevant accounts, but there were stories of heroic and trusting bank managers who honored the payments nevertheless, knowing that eventually the insurance company would cover the IOUs. Ah, those good old days.

Back to the pool once more, from a financial risk management perspective, insurance companies had marked up or loaded their insurance premiums by a sufficient margin to (just barely) cover such a statistical anomaly. For some companies that were particularly hard hit, the actual number of claims exceeded the expected number of claims by up to 50%. In other words, they hadn’t really charged enough in premiums to cover the risk, but those were rare cases and overall companies had enough reserves to cover payouts. I’ll say that the industry’s survival (from the Spanish flu) was a success story for actuarial science. Here is the bottom economic line: The insurance companies charged enough and held enough in reserves to pay claims. Yes, there were some eventual insolvencies and bankruptcies a few years later, but many of those can be blamed on the Great Depression or other isolated calamities before and after 1918.

But here is an important point. The reason the Spanish flu was (somewhat of) a godsend for the insurance industry gets back to the issue of who exactly died. Recall that the 28-year-old men in the Figure were also most likely to be new parents themselves with young children at home. These men were likely to have been breadwinners and their deaths likely resulted in their families being left penniless and indigent.

Those families fortunate enough to own and have life insurance – a practice not yet widespread by any means – meant they had some measure of financial security. But those who died without owning life insurance, whether out of negligence or for reasons of faith, left families destitute at the mercy of the community and society. Remember, this was decades before (the old New Deal) what today is called Social Security in the U.S.

Alas, with the heartbreaking tragedy of death that was experienced in communities all over the U.S., there were financial winners and financial losers. The two distinct groups were quite visible, vocal and rather perversely served as a brilliant advertisement for the insurance industry and the benefits of life insurance. The Spanish flu made mortality risk and life insurance salient. Salient is defined as being notable, conspicuous and standing out. When our attention is drawn to a particular fact or specific item, set against a larger background of noise and distraction, it becomes salient. People noticed the widespread randomness and counter-intuitive mortality rate from the Spanish flu. The risk of an early death became a real possibility, and life insurance was an effective way of protecting against this risk.

According to the National Underwriter, one of the first questions that onlookers would ask at funerals or upon hearing of another tragic death of a young breadwinner was: “Did they have life insurance?” It would be the only solace for a community that was reeling from many other deaths and the financial burdens these imposed. Later, in the 1920s, the insurance industry went even one step further and created advertisements in magazines and newspapers that capitalized on (or some might say took advantage of) the Spanish flu. Marketing departments and executives leveraged the sudden salience of risk – which did not last very long thanks to fading memories – to promote life insurance, a product that previously had not garnered much respect.

As an example, the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company, which is still around today by the way, ran a big advertisement for its life insurance products in the New York Times. The full-page ad was ominous sounding with its emphasis on “sudden”: “Spanish Influenza: Can You Afford Sudden Death?” I presume most people could only afford the gradual kind of death. But in their defense, the insurance industry wasn’t the only group taking advantage of the nascent salience of the Spanish flu to flog commercial and industrial products. Local drug stores and even pharmacists did the same by promoting regular doses of “flaxseed oil as an antidote to the flu.” These advertisements were just as garish as the ones selling life insurance. (P.S. Flaxseed oil doesn’t really do any good.)

Bad Reputation Repaired

The insurance industry had an appalling image in the decade or two before the Spanish flu pandemic, and some might argue it still does. But I can tell you, its reputation was worse then. At the time, its bad reputation was partly because the industry was deeply involved in scandals relating to the sale of (something called) tontine insurance policies. As a result, a substantial segment of the population believed life insurance was a form of gambling, unethical and corrupt. Some argued that sales of something that only pays if you die should be banned on moral grounds, even though many of the policies acted like personal pensions and savings plans. Remember, this was before the Social Security program.

To be crystal clear, people died before the Spanish flu and obviously continued to die after the Spanish flu. Many had life insurance. In fact, approximately 120,000 Americans died in the violence and battles of World War I, most of which were unrelated to the flu. But, high mortality death rates from war was expected and the military cared for its own. Likewise, old people died and some owned life insurance policies, but the financial benefit to the family wasn’t immediate. After all, when a 70-year-old died and a 40-year-old or 50-year-old descendant received a windfall settlement, the societal benefits weren’t as clear.

However, when a 28-year-old-old father (or pregnant mother) died from the Spanish flu, the young family received an immediate and substantial financial disbursement. In this scenario, the social benefits were clear and evident to all. It was one family that wouldn’t have to rely on public (or church) charity. Life insurance products thus gained broad social utility and respectability during the 1920s and 1930s. Nobody questioned the need for, or value of, life insurance when it immediately and evidently relieved the burden of care from the community and extended family. From the 1920s onward, the insurance industry earned a stature and power that persists a full century later.

A full century later whenever some enterprising politician or lawmaker threatens to tinker with any of the tax or regulatory benefits enjoyed by the insurance industry, the retort and defense of the status quo inevitably revolves around references to widows and orphans that will be left destitute.